Northern Goshawk

| Northern Goshawk | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Juvenile (left) and adult by Louis Agassiz Fuertes | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes (or Accipitriformes, q.v.) |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Accipiter |

| Species: | A. gentilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Accipiter gentilis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

| Subspecies | |

|

Accipiter gentilis albidus |

|

|

|

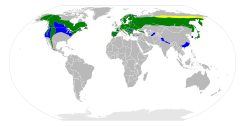

| Range map of Goshawk yellow: breeding green: year-round blue: wintering. |

|

The Northern Goshawk (pronounced /ˈɡɒs.hɔːk/, from OE. góshafoc 'goose-hawk'), Accipiter gentilis, is a medium-large bird of prey in the family Accipitridae, which also includes other diurnal raptors, such as eagles, buzzards and harriers.

It is a widespread species that inhabits the temperate parts of the northern hemisphere. In Europe and North America, where there is only one goshawk, it is often referred to (officially and unofficially, respectively) as simply the "Goshawk". It is mainly resident, but birds from colder regions migrate south for the winter.

This species was first described by Linnaeus in his Systema naturae in 1758 under its current scientific name.[2]

The Northern Goshawk appears on the flag of the Azores. The archipelago of the Azores, Portugal, takes its name from the Portuguese language word for goshawk, (açor), because the explorers who discovered the archipelago thought the birds of prey they saw there were goshawks; later it was found that these birds were kites or Common Buzzards (Buteo buteo rothschildi).

Contents |

Appearance

The Northern Goshawk is the largest member of the genus Accipiter.[3] It is a raptor with short, broad wings and a long tail, both adaptations to manoeuvring through trees in the forests it lives and nests in. Across most of the species's range, it is blue-grey above and barred grey or white below, but Asian subspecies in particular range from nearly white overall to nearly black above. Adults always have a white eye stripe. Males are 49–57 cm (19–22 in) long with a 93–105 cm (37–41 in) wingspan. The female is much larger, 58–64 cm (23–25 in) long with a 108–127 cm (43–50 in) wingspan. Males of the smaller races can weigh as little as 630 grams (22 oz), whereas females of the larger races can weigh as much as 2 kg (4.4 lb). The juvenile is brown above and barred brown below. The flight is a characteristic "five slow flaps – straight glide".

In Eurasia, the male is sometimes confused with a female Sparrowhawk, but is larger, much bulkier and has relatively longer wings. In North America, juveniles are sometimes confused with the Cooper's Hawk. While goshawks average larger, there is overlap in size between small male goshawks and large female Cooper's Hawks, so plumage and structural characteristics need be examined. In North America, the Sharp-shinned Hawk is markedly smaller.

Food and hunting

This species hunts birds and mammals in woodland, relying on its speed of flight through the dense forest as it flies from a perch or hedge-hops to catch its prey unaware. They are usually opportunistic predators, as are most birds of prey. The most important prey species are rodents and birds, especially the Ruffed Grouse in North America, pigeons and doves, and passerines (mostly starlings and crows). Waterfowl up to the size of the Mallard are sometimes preyed on. Prey is often smaller than the hunting hawk, but these birds will also occasionally kill much larger animals, up to the size of snowshoe hares and jack rabbits; prey also include the small raptor, the American Kestrel.[4]

Behavior

In the spring breeding season, Northern Goshawks perform a spectacular "rollercoaster" display, and this is the best time to see this secretive forest bird. At this time, the surprisingly gull-like call of this bird is sometimes heard. Adults return to their nesting territories by March or April and begin laying eggs in April or May. These territories almost always include tracts of large, mature trees that the parents will nest in. The clutch size is usually 2 to 4, but anywhere from 1 to 5 eggs may be laid. The eggs average 59 × 45 mm (2.3 × 1.8 in) and weigh about 60 g (2.1 oz). The incubation period can range from 28 to 38 days. The young leave the nest after about 35 days and start trying to fly another 10 days later. The young may remain in their parents' territory for up to a year of age. Adults defend their territories fiercely from everything, including passing humans, so even the eggs have few predators. Birds of any age may be attacked, rarely, by Bubo owls and large Buteo hawks, but these often cede to or are themselves killed by the aggressive Goshawk.

Status

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the Northern Goshawk became extirpated in the 19th century because of specimen collectors and persecution by gamekeepers, but in recent years it has come back by immigration from Europe, escaped falconry birds, and deliberate releases. The Goshawk is now found in considerable numbers in Kielder Forest, Northumberland, which is the largest forest in Britain. The main threat to Northern Goshawks internationally today is the clearing of forest habitat on which both they and their prey depend. An example of this is the Medicine Bow National Forest which is not only threatened by clearing the forest but is also threatened by ATV riding.

John James Audubon illustrates the Northern Goshawk in Birds of America, Second Edition (published, London 1827-38) as Plate 141 where an adult and juvenile are accompanied by a Stanley Hawk (now Cooper's Hawk). The compound image (made up from more than one original) was engraved and colored by Robert Havell's London workshops. The original watercolor by Audubon was purchased by the New York History Society where it remains. William Lewin illustrates the Northern Goshawk under the title "Goss Hawk" as Plate 9 in volume 1 of his Birds of Great Britain and their Eggs published in London, 1789.

In falconry

The name "goshawk" is a traditional name from Middle English gōshafoc, literally "goose hawk".[5] This implies that they were flown against geese but apparently the name was originally applied to the Peregrine Falcon, a falconers' bird more likely to attack geese.[5]

Northern Goshawks are much used in falconry. "Finnish goshawks" (goshawks from Finland, or their descendants) are prized because they are bigger and stronger than western European native goshawks.

In the Middle Ages, the sparrow hawks were valued for hunting proportionate to their resemblance to the goshawk in size, strength and beauty: a more goshawk-like sparrow hawk could command a higher price. The goshawk is celebrated as a symbol of masculinity in the anonymous eleventh-century poem Las, qu'i non sun sparvir, astur.[6]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2008). Accipiter gentilis. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 19 February 2009.

- ↑ (Latin) Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata.. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii).. pp. 89. "F. cera pedibusque flavis, corpore cinereo maculis fuscis cauda fasciis quatuor nigricantibus."

- ↑ "Northern Goshawk". Birds of Quebec. http://redpath-museum.mcgill.ca/Qbp/birds/Specpages/northerngoshawk.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, ed. 2010. American Kestrel. Encyclopedia of Earth, U.S. National Council for Science and the Environment, Ed-in-chief C.Cleveland

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lockwood, W B (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. OUP. ISBN 978-0198661962.

- ↑ William D. Paden and Frances F. Paden, Troubadour Poems from the South of France (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2007), 20.

Further reading

Identification

- Vinicombe, Keith (2005) Getting to grips with Goshawks Birdwatch 153:29-33 (a discussion of Goshawk identification)

External links

- Northern Goshawk Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Northern Goshawk - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Northern Goshawk Information - South Dakota Birds and Birding

- Environment Canada Goshawk page, including sound clip of Goshawk Call

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Northern Goshawks

- Goshawk videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Picture of Northern & European Goshawk chicks and other Accipiters

- Nature writer recounts goshawk pair's fierce defense of their nesting territory

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta

- "Accipiter gentilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=175300. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- The Medicine Bow National Forest (A Habitat for the Northern Goshawk)-Biodiversity Conservation Alliance